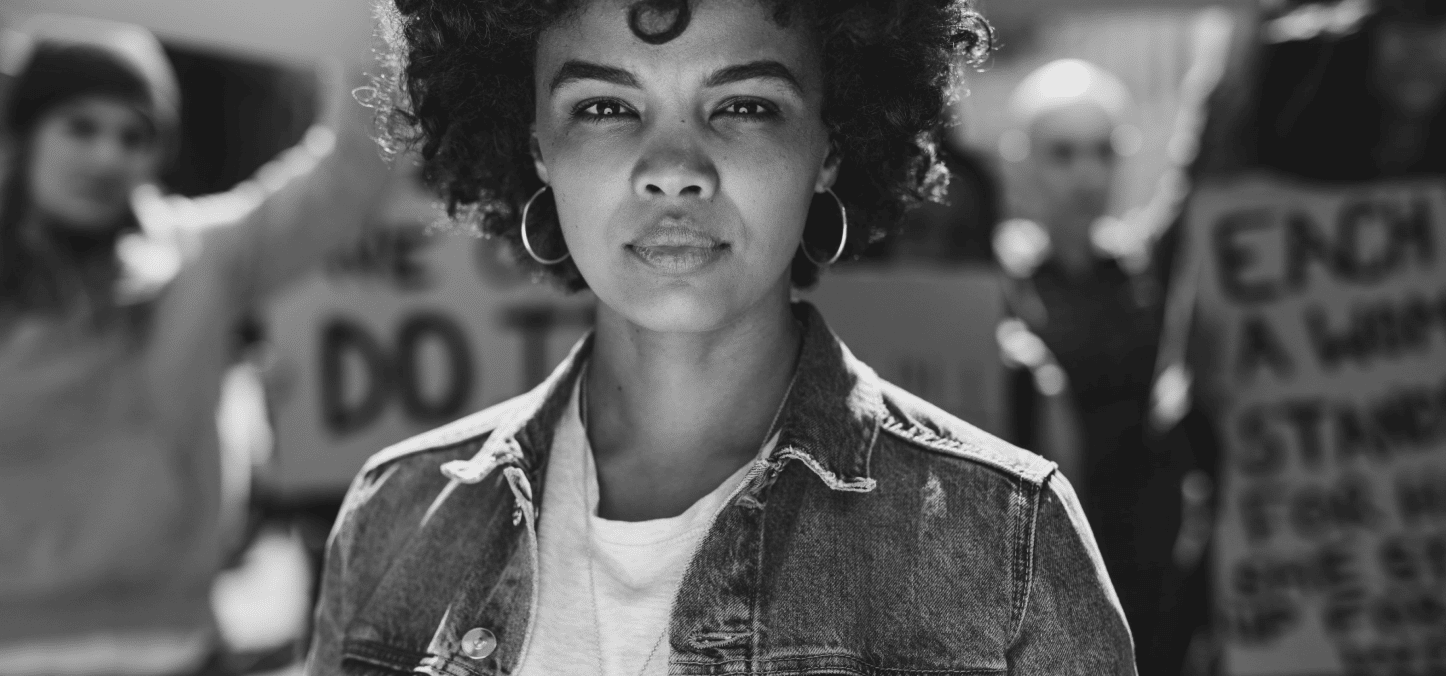

Defending Democracy and Civil Rights in the Courts and in the Streets

About the PCJF

For more than 25 years, the Partnership for Civil Justice Fund (PCJF) has been a leader in the fight to uncompromisingly defend democracy and advance constitutional rights by litigating landmark civil rights and First Amendment cases and providing robust defense to social justice activists and movements. Our work is focused on creating meaningful social and legal changes and dismantling systems of oppression.

PCJF Files Federal Lawsuit Against DC for MPD’s Indiscriminate and Violent Use of Less Lethal Weapons

The Partnership for Civil Justice Fund and its Center for Protest Law & Litigation filed a federal lawsuit against the District of Columbia challenging the Metropolitan Police Department’s “repressive and violent tactics including the authorized indiscriminate use of ‘less lethal’ projectile weapons against peaceful protestors and bystanders, gratuitously and without notice or warning and in order to intentionally retaliate against and inflict pain upon protestors challenging policing in our society.”

The lawsuit seeks to end the MPD’s unconstitutional and punitive tactics of indiscriminately deploying less lethal weapons, including maiming projectiles, into crowds of persons engaged in First Amendment protected activities, in particular those challenging racist police violence.

Featured Issues

PCJF Files Class Action Lawsuit Against San Francisco for its Treatment and Illegal Arrest of More Than 100 Children and Young Adults

The Partnership for Civil Justice Fund filed a federal civil rights class lawsuit against San Francisco and police commanders on behalf of children and young adults arrested in July 2023 at a community event that occurred in Dolores Park in San Francisco, California.

PCJF Files Federal Lawsuit Against DC for MPD’s Indiscriminate and Violent Use of Less Lethal Weapons Against Racial Justice Protests

The PCJF and its Center for Protest Law & Litigation, filed a federal lawsuit against the District of Columbia challenging MPD's “repressive and violent tactics including the authorized indiscriminate use of ‘less lethal’ projectile weapons against peaceful protestors and bystanders."

San José City Council OKs $3.35 Million Settlement for Five Racial Justice Protestors Attacked by San José Police

Racial justice protestors who were attacked and injured by the San José Police Department in May 2020 will receive $3.35 million in a settlement approved by the City Council.

JOIN THE FIGHT

Your support makes sure we can:

- Defend front-line communities waging the fight for justice

- Mount an uncompromising fight back against police repression

- Challenge outrageous suppressive laws

- Expose government misconduct and operations against the social justice movement.

You have made it possible to fight back – and win – including to bring landmark affirmative constitutional rights cases ratifying and expanding the legal recognition of our cherished rights and restricting illegal police tactics.

How you can help

Help us challenge federal and local law enforcement efforts to punish, threaten and silence movements for change. Join us in the fight for democracy, civil rights, and social and environmental justice – in the courts and in the streets.

PCJF Resource Archive

Find litigation documents, FOIAs, Know Your Rights information, and more in our resource library.

Recent News

-

Legal Organizations Condemn Local Repression Against Anti-Genocide Protestors

While peaceful protests were happening in 81 cities and 19 countries, the California Highway Patrol (CHP) took the extraordinary step of jailing the San Francisco protestors on trumped up felony conspiracy charges.

-

Chiu seeks to demonize young people as part of move to dismiss skateboard case

Excerpt from 48 Hills. San Francisco City Attorney David Chiu is asking a federal judge to dismiss lawsuits against…

-

Lawyers for Bay Bridge 78 Call on Court to Dismiss Charges in Interest of Justice

The Center for Protest Law & Litigation at the Partnership for Civil Justice Fund filed a motion in…

-

Four teens sue San Francisco and police chief over mass arrest of youths at ‘Hill Bomb’ skateboarding event

Excerpt from NBC News. Every year, throngs of youths descend upon San Francisco’s Mission District for a skateboarding event, but this year festivities ended in chaos with police arresting over 100 young people.

-

Teens sue San Francisco after mass arrests at skateboarding event

Excerpt from the Washington Post. San Francisco now faces a class-action lawsuit alleging that the roughly 80 juveniles corralled by police were wrongfully detained.

-

Young people arrested in police sweep at Dolores skate event file federal suit

Excerpt from 48 Hills By Tim Redmond | Read the full story here. Attorneys for four young people arrested…